Historical figures

Saint Louis (1214 – 1270)

Louis IX, more commonly known as Saint Louis, ruled France from 1226 until his death in 1270. This Capetian sovereign was known for his pious, reforming character; he changed France from a feudal monarchy to a modern monarchy, by developing royal justice and drawing inspiration from the values of Christianity to promote a just power, founded on a direct relationship between the king and his subjects. He thus strove to become a spiritual and political guide, working for the triumph of justice in civilisation. He attended the construction of many religious buildings, including that of Notre-Dame de Paris, which begun in 1163.

After obtaining the relics of Passion, for which he ordered to build the Sainte Chapelle in 1242, he took part in the seventh and eighth crusades, during which he died of illness. Considered a saint during his lifetime, he was canonised in 1297 by Pope Boniface VII.

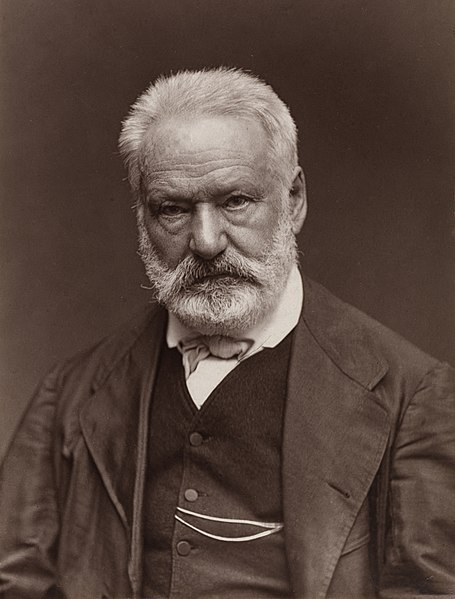

Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885)

A man of letters, politician, and a total and committed poet, Victor Hugo is a major player in the French 19th century… as well as a central figure in the history of Notre-Dame. Indeed, he made this great “book of stone” the eponymous protagonist of his novel Notre-Dame de Paris (better known as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame in its English-language version), whose publication in 1831 triggered a national mobilisation in support of the building. This impetus eventually steered the Minister of Justice and Worship to launch its vast restoration project in 1842.

Known for its grandiloquence, Hugo’s prose cannot but admire the grandeur of this iconic monument of the French Middle Ages, from which romanticism then drew its source of inspiration. Like Viollet-le-Duc, Hugo was a defender of medieval Gothic, associated with the image of the monarchy, and celebrated the magnificence of these buildings whose image it fell to him to restore. Celebrated with great pomp, his funeral at the Pantheon etched his name forever in marble.

A few years ago while visiting, or more accurately, while browsing through Notre-Dame, the author of this book found, in a dark corner of one of the towers, this hand-engraved word on the wall:

’ANÁΓKH.

These Greek capital letters, black with age and quite deeply cut into the stone, I don’t know what signs specific to Gothic calligraphy imprinted in their shapes and in their arrangement, as if to reveal that it was a hand from the Middle Ages which had written them there, especially the lugubrious and fatal meaning they contain, struck the author deeply. […] Since then, we have daubed or scratched away (I don’t remember which one) the wall, and the inscription has disappeared. Because this is how we have acted for almost two hundred years with the marvellous churches of the Middle Ages. Mutilation comes at them from all sides, inside and out. The priest daubs them, the architect scratches them, then the people turn up, who demolish them.

Victor Hugo, préface de Notre-Dame de Paris (1831)

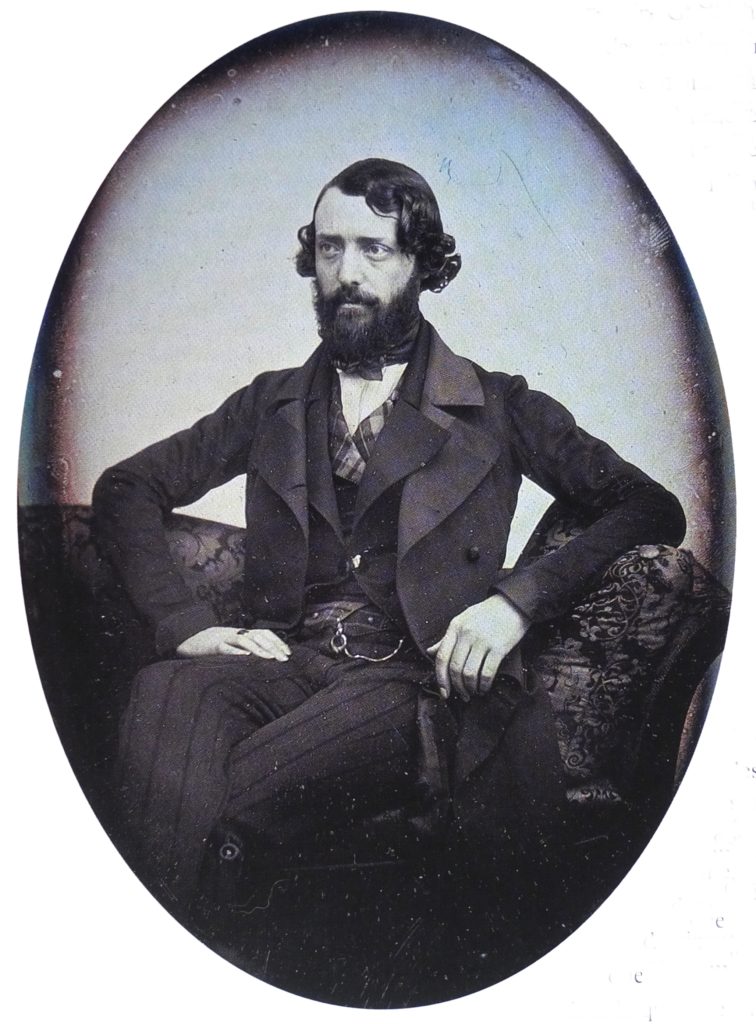

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814 – 1879)

Born in Paris in 1814, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was a major architect of the French 19th century. Truly self-taught, he refused to follow the academic model and trained on the ground, in contact with the monuments of Europe, the forms of which his sketchbooks scrupulously preserve. Close to Prosper Mérimée, then inspector general of historical monuments, he began an atypical career in 1840, made up of controversial restorations and prestigious functions within the State heritage institutions.

In a context of rehabilitation of Gothic art, recognised as national architecture par excellence, Viollet-le-Duc became the herald of a certain medievalism based on rational principles, directly inspired by the builders. He could count on the support of the neo-Gothic battalion, especially the architect Lassus, with whom he restored Notre-Dame.

Selected in 1844, their project returned the cathedral to its former glory while allowing certain additions, designed as extensions to the original building. Thus, the new lead spire, purely ornamental, justified itself by a very personal conception of restoration, which would earn Viollet-le-Duc the wrath of the most rigorous characters of his time. But his work did not stop at the structure of buildings: guided by his organic conception of space, they also integrated elements of furniture, decoration and objects of worship, of which he had versions made in the style of the Middle Ages. These items include the reliquary casket of the Crown of Thorns, the neo-Gothic monstrance and impressive wooden lectern that adorned the cathedral until the fire.

In addition to the traces of his work on French monuments, Viollet-le-Duc’s legacy takes a theoretical form in his magnum opus, the monumental Reasoned Dictionary of French Architecture from the 11th to the 16th century. Published from 1854 to 1858, this work is one of the most influential architectural treatises of the European 19th century. Thus Viollet-le-Duc, far from being a simple “pasticher”, remains one of the great theoreticians of modern architecture.